Nikos Xilouris

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Nikos Xylouris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Psaronikos (Greek: Ψαρονίκος) |

| Born | 7 July 1936 Anogeia, Crete, Kingdom of Greece |

| Died | 8 February 1980 (aged 43) Piraeus, Attica, Greece |

| Genres | Cretan music, Éntekhno |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, Musician, Composer |

| Instrument | Cretan Lyra |

| Years active | 1950-1980 |

| Spouse | Ourania Melampianakis |

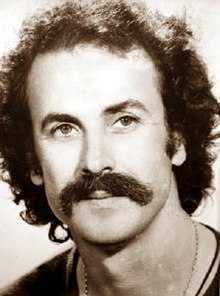

Nikos Xylouris (Greek: Νίκος Ξυλούρης, 7 July 1936 – 8 February 1980), also known by the Cretan nickname of Psaronikos (Ψαρονίκος), was a Greek singer, Cretan Lyra player, and composer, known for performing both rural traditional and urban orchestral music.

Origins and background

[edit]Nikos Xylouris was born in Anogeia, Mylopotamos Province, Rethymno Prefecture, a village on the slopes of <<<Mount Ida (Crete>>> (also known as Psiloritis), the highest mountain on the island of Crete, the largest of the Greek Islands, situated at the southernmost end of the Aegean Sea, and a region known for producing several prominent musicianss.[1]

Xylouris was the fourth child and first son of Giorgis Xylouris, born after sisters Elli, Zoumboulia, and Euridice.[2] His brothers, Antonis Xylouris or Psarantonis[3] (Greek: Ψαραντώνης) and Giannis Xylouris or Psarogiannis (Greek: Ψαρογιάννης) are also celebrated figures of Cretan music, and other members of their extended family continue in this tradition.[4]

Xylouris' nickname "Psaronikos" (with "Psaro" meaning "Fish/Fish-like", plus his given name Niko[lao]s) was inherited from his grandfather Antonis. According to Xylouris, and reiterated by his brother Giannis, Antonis displayed great valor during one of the many instances of the Greek Revolution of 1821 and was said to "consume the Turks as if they were fish."[5][6] The nickname was passed down along the male line of the family, with each person's given name substituting the inaugural one, while the prefix remained.

Another account states that Antonis kept company with a group of Cretans who used guerrilla warfare tactics against the Turks, dispersing and reuniting at predetermined locations after brief engagements. Antonis would "catch up to the rest of them as if they were a school of fish that broke up and then coalesced again; they were as slippery as fish, in waters they knew all too well, and thus impossible to apprehend,"[7] with Antonis himself being the most nimble, frustrating the Turks who could never capture him. Another variation claims he was quick enough to strike at two distant target locations in a single day, disappearing as quickly and efficiently as fish vanish in the sea.[2]

Such nicknames, bestowed for specific traits or actions, are prevalent throughout the Greek countryside, and their familial aspect is often retained to distinguish between clans, branches, or unrelated families with identical surnames. Some nicknames may be unique to specific individuals, reflecting a notable incident in their lives that warrants praise, attention, recognition, or condemnation.

When Xylouris was eight years old, during World War II, the Nazis razed Anogeia to the ground in reprisal for acts of Cretan Resistance against the Axis Occupation, and the casualties the Germans had sustained during the their initial assault on Crete some three years prior. German paratroopers had descended upon the island but were decimated by the locals. The mayor and citizens of Anogeia supported and harbored Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents and Cretan Resistance fighters. Additionally, under Captain William Stanley Moss, Cretans ambushed a detachment German soldiers who had received orders to attack Anogeia.[8] Captain Patrick Leigh Fermor, an SOE operative, had also been in Anogeia during the kidnapping of Heinrich Kreipe in May 1944 but escaped with his band of Cretan partisans when the German forces approached. These acts of defiance led the Germans to target specific villages, sometimes regardless of direct villager involvement.

The razing of Kandanos and the Viannos massacres were similar instances of Nazi atrocities committed in Crete. In the aftermath, the Xylouris family, along with the other inhabitants of Anogeia, were forced to flee to other villages of the Mylopotamos region, and some found refuge in major cities of the island until the Liberation of Crete, which came after the Allied Advance and the German Surrender. Nearly a year after the razing, the damage inflicted upon Anogeia was documented by a scientific committee officially appointed by the newly restored Greek government, including writer Nikos Kazantzakis and Professor Ioannis Kakridis, both remembered for their joint translation of the works of Homer, among other literary endeavors.[9]

Upon returning to Anogeia, citizens had to rebuild their homes and town, imbuing them with a sense of purpose, dedication, self-reliance, solidarity, and pride. Due to the destruction of village archives, some ambiguity remains as to the exact birth dates of all persons lacking additional official documentation, including Xylouris. This is why certain sources may offer conflicting birth dates, although the one mentioned herein is considered the most probable and accurate by consensus, based on village elder and relative testimony. In Xylouris' case, his date of birth coincided with the Greek Orthodox feast of Saint Kyriaki, making the occasion memorable. The unique cultural climate of Crete left lasting impressions on Allied personnel who had served there. In the years following the war, Patrick Leigh Fermor often sang Filedem, (Greek: Φιλεντέμ), which would later become one of Xylouris' most popular songs.[10]

Early life and career in Crete

[edit]At a young age, Xylouris discovered his artistic inclination. All three brothers learned the basics of playing the mandolin and other folk musical instruments with friends at village feasts. He convinced his father Giorgis to purchase him a Cretan Lyra (a three- or four-stringed Cretan fiddle analogue, played upright, usually supported on the knee), a significant investment. Giorgis initially opposed his son becoming a musician, which he considered a menial and disreputable occupation, preferring that he attain higher education to improve his life and escape poverty. However, between the boy's entreaties and the encouragement of local school teacher Menelaos Dramountanis, who recognized Xylouris' potential and considered his singing voice a decisive asset,[2] Giorgis acquiesced, and Xylouris acquired his first instrument at twelve.

After an apprenticeship under lyra player Leonidas Klados, Xylouris started performing at social functions and local festivities, usually accompanied by his younger brother Giannis on the lute.[11] Gifted musicians were generously rewarded at these events by participants who would present the orchestra with banknotes for each requested song or tune. Musicians' reputations grew by crowd acclaim and word of mouth, proven able to please, stir, and entertain their audience, sometimes for days. Having earned a reputation as a skilled musician and aspiring to financial independence, at seventeen Xylouris moved from Anogeia to Heraklion, the largest city in Crete, where he performed nightly at the venue "Kastron" (Greek: Κάστρον). Initially, he struggled to make ends meet, as the urban audience had moved away from Cretan traditional music and had become accustomed to European rhythms, looking down upon the "old people's music" of rural areas. Folk musicians struggled to adapt and survive financially, lacking familiarity with foreign lyrics.

City musicians distrusted newcomers and were unwilling to yield professional space.[12] Xylouris was reluctant to admit his hardships to his father, assuring him to the contrary. Gradually, he developed a following and carved out a niche for himself. His friends and admirers organized gatherings for him to play music, earn a living, and attract support. In 1967, he helped establish in Heraklion the first exclusively Cretan folk music hall, named Erotokritos after the Erotokritos, catering to rural Cretans visiting the city for business or social reasons. These visitors would bring their families and convince their urban acquaintances to join, reviving Cretan folk music in the city.[13] Over time, Xylouris found acceptance as a musician in Heraklion and caused his urban audience to rediscover, appreciate, and preserve Cretan folk music. His second goal was to make that music known beyond Crete, and with his move to Athens, he captivated the Greek national audience[14] and introduced Cretan traditional music to every Greek household. Therefore, he is partially credited with achieving both.[15]

Xylouris' first studio recordings was in 1958 with a 7-inch 45rpm vinyl single featuring "Mia mavrofora otan perna" (When a woman clad in all black passes by | Greek: Μια μαυροφόρα όταν περνά) and "Den klaine oi dynates kardies" (Strong hearts don't cry | Greek: Δεν κλαίνε οι δυνατές καρδιές).[16] Although Odeon Records granted them an audition, executives were worried that Cretan music lacked commercial potential and initially rejected the release. Greek MP from Crete Pavlos Vardinogiannis, who provided Xylouris lodging and was fond of Cretan musical tradition, intervened, vouching for Xylouris and promising to reimburse Odeon for every unsold unit.[16] Odeon relented, and the recording took place with Xylouris' wife Ourania providing supporting vocals. The single was a major success, vindicating Vardinogiannis. Other singles followed with Odeon, but executives remained ambivalent about Xylouris and Cretan music. Later, when Columbia signed Xylouris and his popularity exploded, Odeon tried to lure him back with a lucrative counteroffer. However, Xylouris, placed honor and loyalty before profits and self-advancement, politely turned them down. When Columbia found out about the bid, they improved the financial terms of Xylouris' contract without him requesting a renegotiation.[16]

The turning point in his career came in 1969 with another 7-inch 45rpm vinyl single under the Columbia label, featuring "Anyfantou" (Weaver | Greek: Ανυφαντού) and "Kavgades me to giasemi" (Quarrels with the jasmine | Greek: Καβγάδες με το γιασεμί).[17] The single was a success, and the public's response suggested that prior reservations concerning the appeal of Cretan folk music were unfounded. Xylouris caught the eye of company executives, and his future looked promising. Shortly after, he began making appearances in Athens, which would become his new home.[18] Nevertheless, when Xylouris met with the musicologist and Director for Folk Music Programming at the Greek National Radio Simon Karas, the latter derided Anyfantou and questioned Xylouris' ability to render traditional songs, an opinion which none of the major composers and conductors Xylouris would later work with shared.[19] Ultimately, the Greek National Radio embraced Anyfantou, featuring the song in a special broadcast.[17]

Later life and career in Athens

[edit]Regarding his artistic discovery by the musical establishment of Athens, two views have been put forward. According to one narrative,[12] his career progressed from early appearances in Athens at the Konaki Cretan Folk Music Hall. Musicians who distinguished themselves in Crete were invited to perform for Cretans residing in the Capital. During such a stint, Xylouris met film director and screenwriter Errikos Thalassinos, who introduced him to composer Yannis Markopoulos, who had previously written film score for some of Thalassinos' projects.[20] Markopoulos and Xylouris began a collaboration that spanned the better part of a decade. However, according to Xylouris' wife Ourania,[21][22] Takis Lambropoulos, the head of Columbia Records Greece, first spotted Xylouris singing at a wedding reception in Crete, was moved by his voice, and made a live recording of him. Lambropoulos then sent the tape to composer Stavros Xarchakos, who was living in Paris, to make him aware of his find. Xarchakos would become a close friend to Xylouris and his family. This version is supported by reports in the Athenian Press that Lambropoulos had found "a major new vocal talent" in Crete, as well as the bond formed between him and Xylouris. Xarchakos and Xylouris also had a prolific collaboration, which extended into the theater.

Eventually, Xylouris would work with additional composers and conductors, such as Christodoulos Chalaris, Christos Leontis, and Linos Kokotos, performing poetry by Nikos Gatsos, Yannis Ritsos, Giorgos Seferis, Kostas Varnalis, Dionysios Solomos, Vitsentzos Kornaros, Kostas Karyotakis, Rigas Feraios, Kostas Kindynis, and Kostas Georgousopoulos (a.k.a. Kostas Myris).

Xylouris relocated to Athens during the Greek military junta of 1967–1974, which had come to power after the coup d'état of April 21, 1967. Entertainment not commissioned by the regime offered a respite from its oppressive nature. Youthful audiences flocked to establishments operating around the Acropolis, where Xylouris and other singers performed. Cretan traditional songs, especially Rizitika, previously meant to foster revolution against the Ottomans and sustain hope for Cretan liberation, were repurposed to voice opposition against the Junta and express longing for its demise. Xylouris realized how empowering these songs were for students rebelling against the dictatorship and stood by their side during the Athens Polytechnic School Uprising of 1973, entering the premises and singing songs banned by the Junta, alongside Stavros Xarchakos.[23] Thus, Xylouris became a symbol of hope to the Greek people.[12] His songs were banned from radio and television, and he was summoned to the Greek Military Police Headquarters. Venues that he appeared in were surveilled by operatives of the regime. As a result, his voice became identified not only with Cretan traditional and modern Athenian music but with the movement to restore Democracy.

Composers of the era attempted to blend traditional sounds and instruments with orchestral arrangements and novel poetic works. This genre of music was uplifting to Greeks, who needed a different cultural environment than the one the Junta offered. At the same time, around 1971, Greek intellectuals sought to convey anti-dictatorial messages with the opportunity of the 150th Anniversary of the Greek Revolution of 1821, while the Junta aimed to exploit the same occasion for pro-regime propaganda. The theater company of Tzeni Karezi and Kostas Kazakos commissioned playwright Iakovos Kambanellis, a survivor of the Mauthausen concentration camp and later member of the Academy of Athens, to write a retrospective of modern Greek history, scored by Xarchakos, who offered Xylouris the part of the main singer. The result was the play "To Megalo Mas Tsirko" (Our Great Circus | Greek: Το Μεγάλο μας Τσίρκο), staged at the Athinaion Theater, which enjoyed success. Slogans used in the play, such as Psomi - Paideia - Eleftheria (Bread - Education - Freedom | Greek: Ψωμί - Παιδεία - Ελευθερία) and Foni Laou - Orgi Theou (Voice of the People - Wrath of God | Greek: Φωνή Λαού - Οργή Θεού) were adopted by protesting university students, became linked with their uprising, and found their way into the Greek Nation's collective consciousness after the restoration of Democratic rule in 1974.

Following the restoration of Democracy, Xylouris released additional albums with Markopoulos and Xarchakos and continued to make live appearances and concerts. In the days after the fall of the Junta, he participated in the liberation concert immortalized as Tragoudia tis Fotias (Songs of Fire | Greek: Τραγούδια της Φωτιάς) by director Nikos Koundouros, before the Athenian audience.

Public and critical acclaim

[edit]In 1966, Xylouris represented Greece at the San Remo Music Festival and won First Prize in its Folk Music Section. In 1971, he was awarded the Grand Prix du Disque by the Académie Charles-Cros in France for his performance of the Cretan Rizitika album with Yannis Markopoulos.

Personal life and family

[edit]Xylouris met his wife Ourania Melampianakis at a festival in her native village of Venerato, where he was performing. The pair only exchanged glances, due to local courtship customs.[24] Ourania came from an affluent family, while Xylouris was seen as an itinerant musician. Although Cretan society did not enforce strict class segregation, pairings viewed as socially unequal were frowned upon. In the following months, Xylouris would serenade Ourania regularly[25] a custom shared by many medievally Italian-occupied areas of Greece and which many male youths of Crete would often perform to woo the young ladies they admired.

Eventually, Xylouris proposed to Ourania, and the pair eloped heading for Anogeia where the wedding would occur. Although her father did assent to the marriage, Ourania was ostracized by her family for the elopement, creating a lifelong psychological wound. Eventually, Ourania and her family reconciled after her husband's career took off.

The couple had two children, a son named Giorgis (George) and a daughter named Rinio (Irene), and remained married until Xylouris' passing. Ourania has maintained her mourning (Greek: πένθος) ever since and never remarried.

The couple's love story echoes the Erotokritos by Vitsentzos Kornaros, select verses of which were sung by Xylouris in one of his albums.[26]

Illness and death

[edit]Nikos Xylouris died of lung cancer and metastasis to the brain on 8 February 1980, in Piraeus, Greece, and was interred at the First Cemetery of Athens.[27]

Discography

[edit]- Mia mavrofora otan perna — Μια μαυροφόρα όταν περνά (1958)

- Anyfantou — Ανυφαντού (1969)

- O Psaronikos — Ο Ψαρονίκος (1970)

- Mantinades kai Chorοi — Μαντινάδες και χοροί (1970)

- Chroniko — Χρονικό (1970)

- Rizitika — Ριζίτικα (1971)

- Dialeimma — Διάλειμμα (1972)

- Ithageneia — Ιθαγένεια (1972)

- Dionyse kalokairi mas — Διόνυσε καλοκαίρι μας (1972)

- O Tropikos tis Parthenou — Ο Τροπικός της Παρθένου (1973)

- O Xylouris tragouda yia tin Kriti — Ο Ξυλούρης τραγουδά για την Κρήτη (1973)

- O Stratis Thalassinos anamesa stous Agapanthous — Ο Στρατής Θαλασσινός ανάμεσα στους Αγάπανθους (1973)

- Perifani ratsa — Περήφανη ράτσα (1973)

- Akolouthia — Ακολουθία (1974)

- To megalo mas tsirko — Το μεγάλο μας τσίρκο (1974)

- Parastaseis — Παραστάσεις (1975)

- Anexartita — Ανεξάρτητα (1975)

- Komentia, i pali chorikon kai vasiliadon — Κομέντια, η πάλη χωρικών και βασιλιάδων (1975)

- Kapnismeno tsoukali — Καπνισμένο τσουκάλι (1975)

- Ta pou thymoumai tragoudo — Τα που θυμούμαι τραγουδώ (1975)

- Kyklos Seferi — Κύκλος Σεφέρη (1976)

- Erotokritos — Ερωτόκριτος (1976)

- I symfonia tis Gialtas kai tis pikris agapis — Η συμφωνία της Γιάλτας και της πικρής αγάπης (1976)

- I eleftheri poliorkimeni — Οι ελεύθεροι πολιορκημένοι (1977)

- Ta erotika — Τα ερωτικά (1977)

- Ta Xyloureika — Τα Ξυλουρέικα (1978)

- Ta antipolemika — Τα αντιπολεμικά (1978)

- Salpisma — Σάλπισμα (1978)

- 14 Chryses Epitichies – 14 Χρυσές Επιτυχίες (1978)

Posthumously released material

[edit]- Teleftaia ora Kriti — Τελευταία ώρα Κρήτη (1981)

- Nikos Xylouris — Νίκος Ξυλούρης (1982)

- Pantermi Kriti — Πάντερμη Κρήτη (1983)

- O Deipnos o Mystikos — Ο Δείπνος ο Μυστικός (1984)

- Stavros Xarchakos: Theatrika — Σταύρος Ξαρχάκος: Θεατρικά (1985)

- O Yiannis Markopoulos ston Elliniko Kinematografo — Ο Γιάννης Μαρκόπουλος στον Ελληνικό Κινηματογράφο (1988)

- I synavlia sto Irodio 1976 (1990) — Η συναυλία στο Ηρώδειο 1976 (1990)

- To chroniko tou Nikou Xylouri — Το χρονικό του Νίκου Ξυλούρη (1996)

- Nikos Xylouris — Νίκος Ξυλούρης (2000)

- I psychi tis Kritis — Η ψυχή της Κρήτης (2002)

- Itane mia fora... — Ήτανε μια φορά... (2005)

- Tou Chronou Ta Girismata — Του Χρόνου Τα Γυρίσματα (2005)

- Itane Mia Fora... Kai Emeine Gia Panta! — Ήτανε Μια Φορά... Και Έμεινε Για Πάντα! (2017)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The village of Anogeia produces creators of music - Τα Ανώγεια βγάζουν δημιουργούς". kathimerini.gr. 27 January 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Nikos Xylouris: Our spirit | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: Η πνοή μας". www.gazzetta.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Antonis Xylouris (Psarantonis) – Artists from Anogia – History – MUNICIPALITY OF ANOGEIA". Anogeia.gr. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "Three Xylouris generations in one movie - Τρεις γενιές Ξυλούρηδες σε μια ταινία". thetoc.gr. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris: the angelic voice and the short life of the superb artist | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: Η αγγελική φωνή και η σύντομη ζωή του τεράστιου καλλιτέχνη". athensmagazine.gr. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Μπαλαχούτης, Κώστας (10 October 2022). "Why the Xylouris brothers are called Psaronikos, Psarantonis, Psarogiannis | Γιατί τους Ξυλούρηδες τους λένε: Ψαρονίκο, Ψαραντώνη, Ψαρογιάννη". odgoo.gr. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris – Artists from Anogia – History – MUNICIPALITY OF ANOGEIA". Anogeia.gr. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Beevor, Antony. Crete: The Battle and the Resistance, John Murray Ltd, 2005.

- ^ Ψαρουλάκης, Γιώργος (14 August 2015). "71 years since the Holocaust of Anogeia | 71 χρόνια από το Ολοκαύτωμα των Ανωγείων". Νέα Κρήτη (in Greek). Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Filedem! Born 100 Years Ago Today". Patrickleighfermor.org. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "Giannis Xylouris (Psarogiannis) - Municipality of Anogeia | Γιάννης Ξυλούρης (Ψαρογιάννης) - Δήμος Ανωγείων". anogeia.gr (in Greek). 25 September 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Biographies: Nikos Xylouris | Βιογραφίες: Νίκος Ξυλούρης". SanSimera.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "35 years without Nikos Xylouris - Why he is called the "Archangel of Crete" | 35 χρόνια χωρίς τον Νίκο Ξυλούρη - Γιατί τον λέμε «Αρχάγγελο της Κρήτης»". ekriti.gr (in Greek). 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris: a figure that identifies with pride, benevolence, and the human fighting spirit | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: Μια μορφή ταυτισμένη με την περηφάνια, την ανθρωπιά, την αγωνιστικότητα". Ημεροδρόμος. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Γεωργούλα, Διδώ (8 February 2022). "Archives of the Hellenic National Television: Nikos Xylouris - February 8th 1980 | Αρχείο της ΕΡΤ: Νίκος Ξυλούρης - 8 Φεβρουαρίου 1980 - ERT.GR". www.ert.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "The rejection of Nikos Xylouris by the records company, and the intervention of Pavlos Vardinogiannis for the first record to be released. | Η απόρριψη του Νίκου Ξυλούρη από τη δισκογραφική εταιρία και η παρέμβαση του Παύλου Βαρδινογιάννη για να βγει ο πρώτος του δίσκος". ΜΗΧΑΝΗ ΤΟΥ ΧΡΟΝΟΥ (in Greek). 10 July 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b Γιώγλου, Θανάσης (8 February 2022). "Nikos Xylouris' "Anyfantou" on National Radio | Η ραδιοφωνική «Ανυφαντού» του Νίκου Ξυλούρη". ogdoo.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Civic initiative in Athens aiming to name future Metro Railway station after Nikos Xylouris | Δράση πολιτών στην Αθήνα για την ονομασία μελλοντικού σταθμού του Μετρό σε «Νίκος Ξυλούρης»". ΑΝΩΓΗ (in Greek). 25 February 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Αρναουτάκης, Βαγγέλης (29 November 2012). "Nikos Xylouris - A lyra player counts the stars | Νίκος Ξυλούρης – «Ένας λυράρης μετράει τ' άστρα»". ogdoo.gr. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Errikos Thalassinos - Resume | Ερρίκος Θαλασσινός - Βιογραφικό". www.ishow.gr. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris: Biography, lyrics and songs | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: Βιογραφία, στίχοι και τραγούδια". stixos.eu (in Greek). Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris: Resume | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: Βιογραφικό". www.ishow.gr. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "When Nikos Xylouris was united with the people and youth of the Polytechnic | Όταν ο Νίκος Ξυλούρης ενώθηκε με το λαό και τη νεολαία του Πολυτεχνείου". Alfavita (in Greek). 17 November 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "When destitute Nikos Xylouris was forced to elope with his beloved Ourania who hailed from an affluent family: her father provided his consent, but stopped being on speaking terms with her. | Όταν ο πάμφτωχος Νίκος Ξυλούρης αναγκάστηκε να κλέψει την αγαπημένη του Ουρανία, που προερχόταν από εύπορη οικογένεια: ο πατέρας της συναίνεσε αλλά σταμάτησε να της μιλάει". ΜΗΧΑΝΗ ΤΟΥ ΧΡΟΝΟΥ (in Greek). 7 February 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Ourania Xylouris: a Rare Interview about Nikos Xylouris | Ουρανία Ξυλούρη: Σπάνια Συνέντευξη για τον Νίκο Ξυλούρη". art-retro.gr. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Καψαλάκης, Ζαχαρίας (17 June 2022). "When Nikos Xylouris eloped with his Ourania - a love story seemingly leaping out of the Greek Cinema. | Όταν ο Νίκος Ξυλούρης έκλεψε την Ουρανία του - μια ιστορία αγάπης σαν από Ελληνική Ταινία". e-mesara (in Greek). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Nikos Xylouris: 40 years without the "Archangel of Crete" | Νίκος Ξυλούρης: 40 χρόνια χωρίς τον «Αρχάγγελο της Κρήτης»". antenna.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 21 June 2022.